The Book of Rain featured in the Edmonton Journal’s Top Five Books of 2023.

The Book of Rain has been chosen as a finalist for the 2023 Atwood Gibson Writers’ Trust Prize.

I wrote an article for Hazlitt Magazine about how and why realist fiction needs a rewilding, and how a new generation of writers, like the brilliant Jordan Abel, are doing just that.

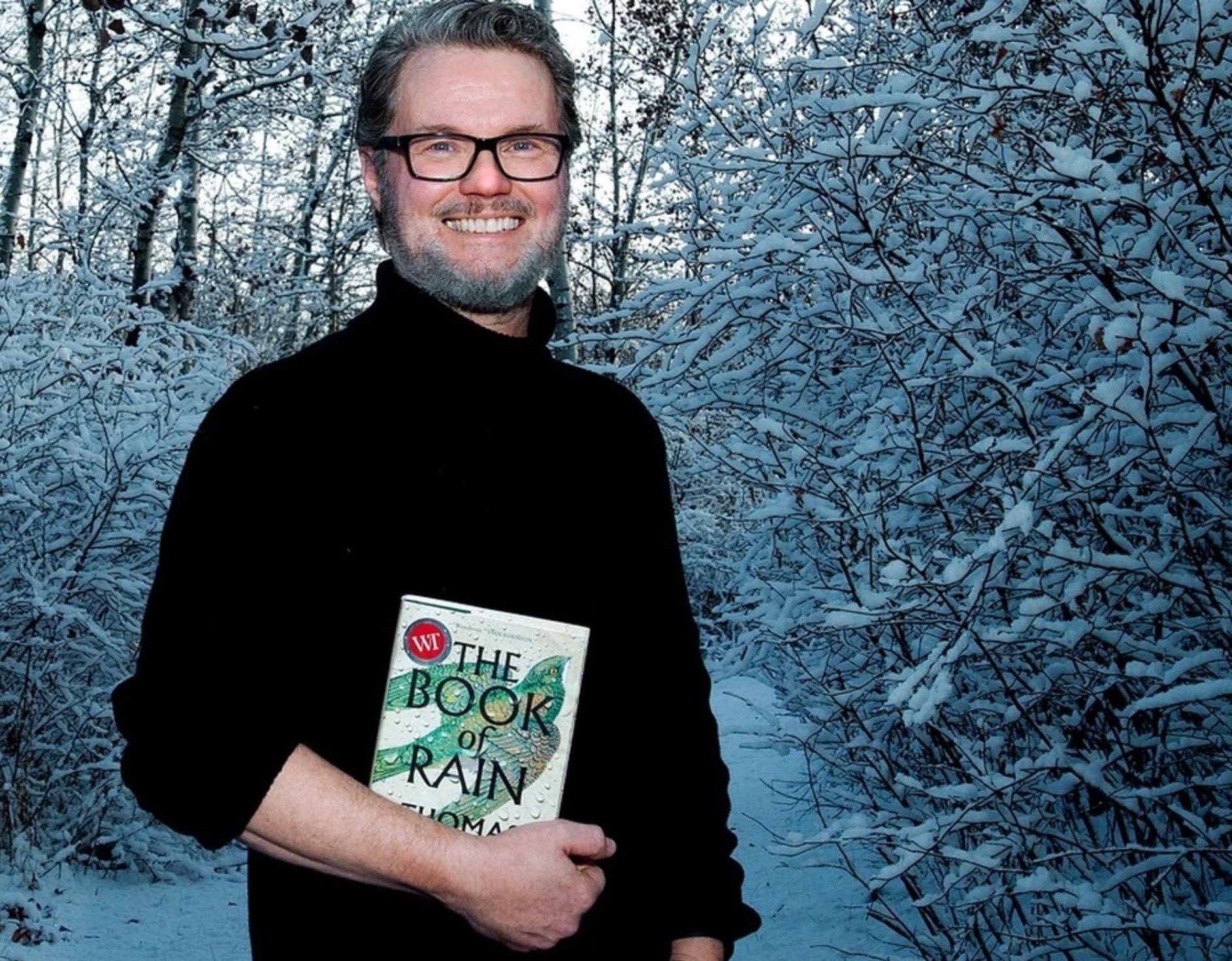

Image by Glenn Harvey

The Book of Rain reviewed by Jonathan Ball in the Winnipeg Free Press

The Book of Rain reviewed by Allan Hepburn in The Literary Review of Canada.

The Book of Rain featured in “30 Canadian Books to Get Your Dad for Father’s Day”

Jamie Portman interviews me about The Book of Rain, National Post newspapers, March 25 2023

The Book of Rain

featured in CBC Books

Russian-language publisher Everbook has picked up world Russian rights to The Book of Rain for their new fiction imprint, The House of Stories.

Advance praise for

The Book of Rain

“It’s difficult to describe just how audaciously imaginative The Book of Rain is. Thomas Wharton has crafted a world parallel to this one yet not, an epic of consuming scope…. A stunning excavation of how fragile, fleeting, and many-faced it is to be human. I wish more books surprised me as much as this one did.” — Omar El Akkad

“Wharton’s unflinching eye and soaring imagination turns a perilous journey wondrous.” — Eden Robinson

“The Book of Rain isn’t so much a book as it is and ecosystem … the reader comes away from it astonished and fulfilled.” — Amanda Leduc

'“ … a kind of miracle, one I’m glad I had an opportunity to experience.” — Craig Davidson

THE BOOK OF RAIN

THE BOOK OF RAIN

My new novel The Book of Rain will be released in Canada on March 14 2023.

-

May 2022: My short story “Vanishing Act” is shortlisted for the Alberta Magazine Publisher awards.

-

February 2022: Valentin Baillehache of Editions Payot & Rivages has picked up World French rights ex-North America to my forthcoming novel, THE BOOK OF RAIN, which will be released in English in Canada by Random House in spring 2023.

-

My upcoming novel, The Book of Rain, will be published in a French translation by Editions Alto, Quebec, in spring 2023.

-

Oct 2021: The new Landmark edition of my first novel, Icefields, is now available from NeWest Press. The manuscript has been fully revised and the new edition features an Afterword by Suzette Mayr and an interview with me by Smaro Kamboureli.

-

My upcoming novel, The Book of Rain, will be published in spring 2023 by Random House Canada.

-

The Ice is Alive

A found poem for the launch of the new Landmark edition of Icefields, October 2021. (Passages taken from the novel)

“As if everything in the world is the history of ice.”

—Michael Ondaatje, Coming Through Slaughter

######

I sometimes have the feeling the ice is alive.

The high plain of snow and ice from which the glaciers descend, cannot be seen from the valley. It must be imagined.

Squinting, he picked out the crevasses and icefalls of Arcturus glacier. From this distance they seemed only delicate, spidery wrinkles in pale blue silk. Above them gleamed the white rim of the névé, where the glacier spilled from a gap between the flanking peaks. A slender curve of burning snow.

The branches of the trees near the terminus all grow to one side of the trunk, away from the knife wind blowing off the ice. Ragged pennants.

Stones, fragments of a lost continent, lie scattered in the dirty snow of the till plain. A shattered palette at my feet, the mad artist having just stalked away. Grey breccia flecked with acid green and primrose yellow. Pock-marked slabs into which powder of burnt sienna has been ground. The many-coloured constellations of lichen growth: rocks splattered with alizarin crimson and cadmium orange. The purple and white veins of limestone.

The enchantment of these mute fragments is undeniable.

I sometimes have the feeling the ice is alive.

Moraine: Rock debris deposited by the receding ice: a chaotic jumble of fragments, from which history must be reconstructed.

After an hour the sun has risen overhead and climbs with him, now an enemy. The ice weakens, sloughs off its brittle outer skin, releasing itself into liquid all around him. He is climbing an emerging waterfall.

There can be little doubt the glacier is at present retreating. The logical next step is to determine as closely as possible the flow rate and the average yearly amount of recession.

By doing so, one should be able to predict the approximate time it would take an object imbedded at a particular location in the ice to travel to the terminus and melt out.

NUNATAK:

An island of rock rising above the surrounding ice, upon which one may discover the tenuous presence of life.

As I watch, a wide crater-like depression on the glacier slowly fills with water. By early evening it has become a lake, perfectly transparent, filled with the purest water on earth. There are no fish in its depths, no sedges or grasses along the shore. No geese, no shore birds gather here at dusk.

Each night, as the meltwater lessens, the lake subsides. In the morning it has vanished again.

As the glacier flows forward, its topography will inevitably change, and the lake will vanish. For that reason, its ephemerality, I see no reason to give this body of water a name. It will remain the ideal lake.

In certain rare conditions of wind and sunlight, glacial ice evaporates immediately, without passing through the liquid stage. This is called sublimation, a more refined form of melting.

The phenomenon is often accompanied by a rhythmic crackling sound, as if invisible feet were stepping across the ice.

The sun here sends forth billowing streamers and scintillant curtains of radiance. On the earth this light acts strangely: it has substance, life: it bobs, spills, dances, changes direction. It appears and disappears suddenly, changing the colour and shape of objects in front of your eyes.

To study accurately the variations in temperature and flow rate, it was necessary to live on the glacier for several consecutive days.

When the temperature drops at dusk to below zero, all the streams on the glacier surface cease to flow. Everywhere the ice bristles up with glittering frost needles as the melted and now refreezing surface water dilatates. A garden of tiny ice flowers seems to be growing all around me.

Glacial ice is not a liquid, nor is it a solid. It flows like lava, like melting wax, like honey. Supple glass. Fluid stone.

To watch it flow, one must be patient. There are few changes that can be seen in the course of one day. But over time crevasses split open and others close. There are ice quakes that shift the terrain, unpredictable geysers of meltwater that carry away aiguilles and other landmarks. And of course the evidence of flow, acts of delicate, random precision: shards of rock are plucked by the ice from their strata, carried miles downstream, and left lying with fragments from another geological age.

I see a rippling pool on the bleached surface of the nunatak and the sparsity of the landscape draws me to it.

Water.

The pool is perfectly transparent, fringed with a crust of spring ice. Fed by a thin rivulet that spills with the clarity of music from the glacier. I cup my hands and drink.

I lean back on the sun-warmed rock, close my eyes, and listen. The glacier moves forward at a rate of less than one inch every hour. If I could train myself to listen at the same rate, one sound every hour, I would hear the glacier wash up against this rock island, crash like waves, and become water.

The ablation zone, between the inviolate and the melting regions of the glacier, is often sharply defined.

Once past this point the ice begins to die.

It’s melting can be hastened by even a faint increase in heat at the lower extremity of a glacier, such as produced by the flash bulbs of hundreds of cameras.

The icefield is the source of several major river systems, and a storehouse of fresh water. The layers of ice deep within the field may be hundreds of years old, formed from snow that fell here before the discovery of America, before the birth of Shakespeare, before the industrial revolution.

Some scientists believe that it is to the effects of the most recent ice age we owe the emergence of civilization.

The onset of this glacial epoch, hundreds of thousands of years ago, must have brought catastrophic change to the earth’s surface. Previously lush vegetation dwindled. Many animal species vanished, evolved, or migrated. The early tribes of humans, once simple hunters and gatherers, were forced into a nomadic existence, into the unknown, and they needed new tools for the journey. New ways of thinking. New words.

The transition zone between two worlds.

The terminus of the glacier is an instructive place. Ceaselessly changing, and yet always the same, like the seashore. Ice streams becoming rivers, mountains wearing down into valleys.

The transition zone between two worlds.

Immense pressure, coupled with extreme cold. Combining to produce hitherto unknown effects on matter. Or upon spirit.

The possibility of a spiritual entity trapped, frozen, in ice. Enmeshed somehow in physical forces, immobilized, and thus rendered physical and solid itself.

And when it melted out of the ice, would it then just sublimate back into metaphysical space, leaving human time and scientific measurement behind?

Orchids do not grow here. Nothing grows here. The unceasing collision of ice and rock grinds away all life. Nothing can survive at the terminus.

--And yet, even now, I sometimes have the feeling the ice is alive.

At the foot of the glacier I halt again to catch my breath. I hear the faint creak of ice pinnacles nudged by the wind.

Come with me. I want to show you something extraordinary.